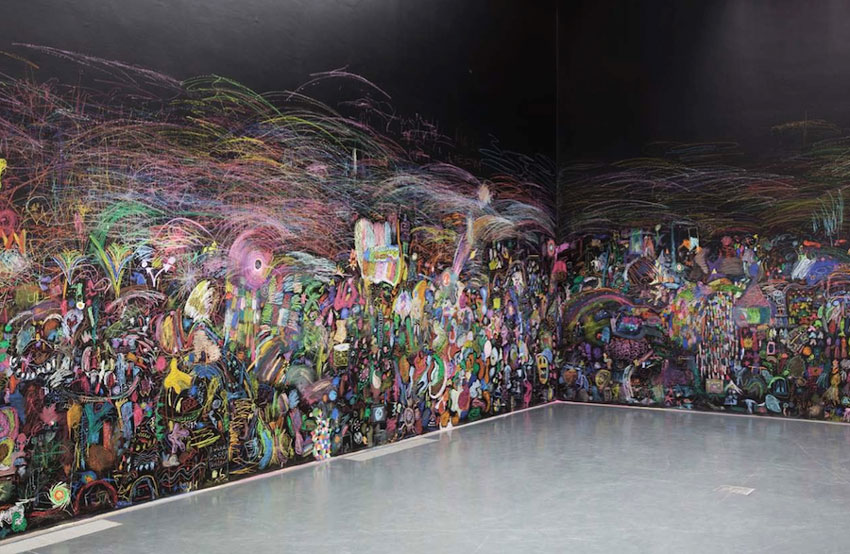

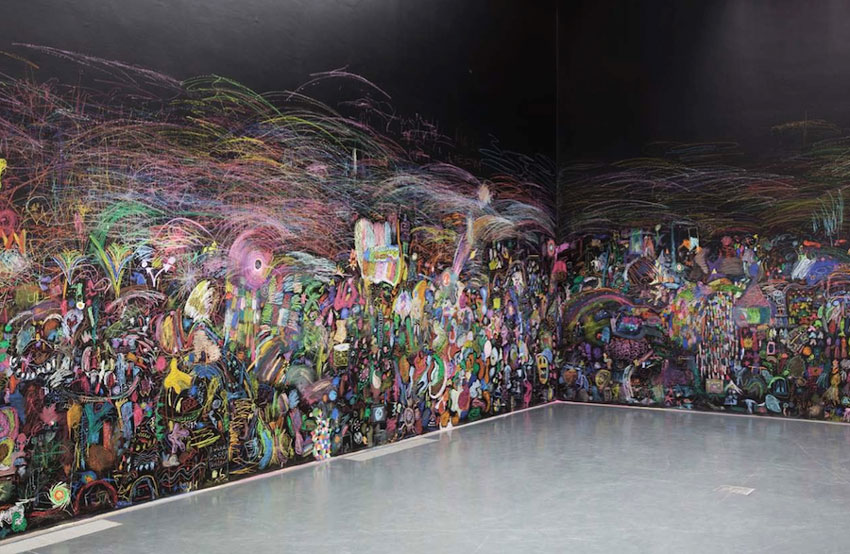

Matteo Rubbi, ‘Blackboards’ (2011)

Through a workshop involving two primary schools, a physicist and some artists, the young pupils attempt to portray the complexity of the world as it is described by quantum mechanics.

Matteo Rubbi, ‘Blackboards’ (2011)

Through a workshop involving two primary schools, a physicist and some artists, the young pupils attempt to portray the complexity of the world as it is described by quantum mechanics.

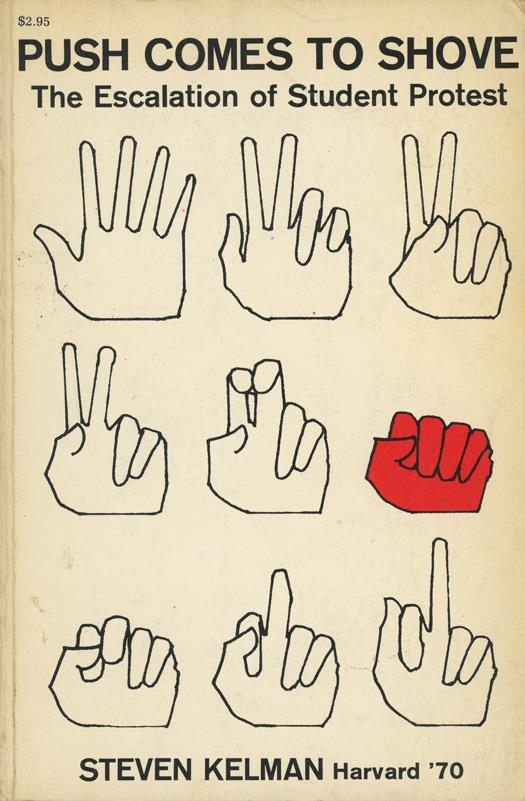

Jello Biafra‘s cover illustration for Steven Kelman‘s ‘Push comes to Shove: The Escalation of Student Protest’ (1970)

Christian Marclay, ‘Mixed Reviews (American Sign LAnguage)’ (2006)

This video takes writing about music as its theme, and depicts American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter Jonathan Kovacs signing a long, collaged text made by Marclay from reviews of musical performances and records.

‘Pilgrimage of the Epileptics to the Church at Molenbeek’, by Pieter Breughel the Younger.

Dancing mania (also known as dancing plague, choreomania, St John’s Dance and, historically, St. Vitus’ Dance) was a social phenomenon that occurred primarily in mainland Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries. It involved groups of people dancing erratically, sometimes thousands at a time. The mania affected men, women, and children, who danced until they collapsed from exhaustion.

The outbreaks of dancing mania varied, and several characteristics of it have been recorded. Generally occurring in times of hardship, up to tens of thousands of people would appear to dance for hours, days, weeks, and even months.

Bartholomew notes that some “paraded around naked” and made “obscene gestures”. Some even had sexual intercourse. Others acted like animals, and jumped, hopped and leaped about. They hardly stopped, and some danced until they broke their ribs and subsequently died. Throughout, dancers screamed, laughed, or cried, and some sang. Bartholomew also notes that observers of dancing mania were sometimes treated violently if they refused to join in. Participants demonstrated odd reactions to the colour red; in A History of Madness in Sixteenth-Century Germany, Midelfort notes they “could not perceive the color red at all”, and Bartholomew reports “it was said that dancers could not stand… the color red, often becoming violent on seeing [it]”. Bartholomew also notes that dancers “could not stand pointed shoes”, and that dancers enjoyed their feet being hit.

More here.